Jolliffe, John (McKechnie Section 3)

See also Sections One and Two

Recorded by Jackson (Dictionary) under his surname only. In another reference, however, Jackson (and also Mills and Coke) attributed Jolliffe's work to H. P. Roberts, the name of one of the artist's sitters, seen inscribed on the reverse of one of his silhouettes. The confusion was resolved by W. P. Perkins, who found a labelled example, painted in the same style, clearly marked as being by Jolliffe; this established what the artist's surname was. Recent research has revealed not only Jolliffe's full name, but the names of his parents also, as well as new information about his life and the date of his death.

Jolliffe was one of the earliest commercial profilists, as we know from the Correspondence of Thomas Gray and William Mason (London, 1853). In 1758 Gray received from his friend the Reverend William Mason a copy of some verses, with a request for criticism of them. The verses were entitled 'An Ode to Mr. Jolliffe who cuts out likenesses from the Shadow at White's'. (White's is the famous club in St James's Street, London, founded in 1693 by Francesco Bianco). The text of the poem runs as follows:

Oh, thou that on the walls of White's

The temple of virtu,

Of dukes and earls, and lords and knights,

Portrayest the features true!

Hail, founder of the British school!

No aids from science gleaning.

Let Reynolds blush, ideal fool,

Who gives his pictures meaning.

Of taste and manners let him dream,

With all his art and care,

He can but show us what men seem,

You show us what they are.

Let connoisseurs of colouring talk,

What is't at best but skin:

You, Jolliffe, at one master-stroke,

Display the void within.

In his reply Gray wrote, 'I am extremely pleased with your fashionable ode.' He went on to offer a few criticisms (the revised text which I have quoted incorporates at least one of these) and also inquired who Jolliffe was. 'Lord,' replied Mason, 'you are not one of us; you know nothing of life. Why, Mr. Jolliffe is a bookseller's son in St. James' Street, who takes profiles with a candle better than anybody. All White's have sat to him, including Prince Edward. At first his price was only half a crown, but now it is raised to a crown, and he has literally got a hundred pounds by it.'

We know from this that by 1758 Jolliffe must have cut at least eight hundred profiles. He was probably about twenty years old at this time. 'Prince Edward' must have been Edward Augustus, Duke of York and Albany (1739-67), third child and second son of Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales. C. E. Vulliamy (Royal George, London, 1937) describes him as 'a careless depraved young man — George III kept him at a distance.'

Mr Percy Higgs has discovered that Jolliffe's family lived at 72 St James's Street for many years. This house was at the lower end of St James's Street on the west side, opposite King Street and next door to Arthur's Club. It was occupied by the Jolliffes from at least as early as 1741 until 1795, when it became No. 70 (the numbering of the houses in the street changed in that year). The profilist's father, John Jolliffe, died in February 1755. From 1741 until his death he had paid the poor rate, as householder. From 1756 his wife Jane paid the rates, continuing to do so until 1780 (possibly the year of her death). The profilist may have been born in this house.

Gray referred to Jolliffe as a bookseller's son. The bookselling business must have existed in 1758, but the earliest directory references date from 1774. After John Jolliffe's death, the business may have been carried on by his widow. No doubt her profilist son discovered that the production of profiles was more profitable, although he may have assisted in the family business. A search of wills at Somerset House, of the records of St James's Church, Piccadilly, and of the records in the Westminster Archives Library revealed only one reference to the Jolliffe family: the date of W. J. Jolliffe's death (May 1798). I own two lockets by him, dated 1797, which indicate that he was working up to within a year of his death. He was probably in his sixties when he died.

Jolliffe's profiles on glass are skilful and individual, but rarely labelled or signed. All the cabinet size pieces which I have seen are painted on flat glass. The earliest illustrated silhouette (in Chapter Four) is a profile of a man wearing a three-cornered hat (possibly the Kevenhuller hat of the late 1760s). This sillhouette is backed with silk; the glass is decorated with a plain black band, on the inner side of which is an oval of black dots.

94

A few other artists were to use a similar decorative band, but at a later date, and Jolliffe was probably the first profilist to use this technique. He was to use it often, with variations. He continued to back his glass profiles with silk; often he decorated the black surround with large dots and scrolls, all drawn 'with a needle and backed with gold or with copper foil, to give an effect of specks of gold round the portraits. Sometimes Jolliffe elaborated the decoration by depicting elegant lacy curtains, painted with thinned pigment, inside the elaborate bands.

Jolliffe used the needle, sometimes to show the detail of the sitter's hair, and always to show the lines marking the sleeves, collars and lapels of men's coats. When rendering the transparent materials of women's dresses of the 1790s, Jolliffe usually scratched wavy parallel lines. He sometimes combined this scratching with brush-strokes so skilfully that, seen against the silk backing, the work has the effect of a needlework picture.

As a rule, Jolliffe continued his portraits to the base of the oval decorated surround, but a few examples are terminated with an almost horizontal bust-line finish. In some cases Jolliffe continued the profile to the base of the glass, thus obliterating the oval decoration (which he would have painted first). Most of the decoration in the bands was originally backed with foil, but an inspection of dismantled examples shows that the metal foil (of pinkish hue when copper was used) was applied in large pieces, which, over the years, have peeled and largely disintegrated. A greenish hue behind these dots indicates the presence of verdigris, caused by the deterioration of the copper. I have not seen silhouettes by any other artist on which copper is used in this way.

Some of Jolliffe's women sitters have a doll-like look; his silhouette of Mary Drewe (in my collection) lacks decorative bands, although it is backed with silk, but is identifiable from this doll-like appearance as well as from the style of work with the needle. The silhouette of a little girl (c. 1794-95) illustrated in Chapter Eight shows Jolliffe's style at its most delicate and finished.

245

Three lockets by Jolliffe are illustrated. They are all typical of his style and have the decorative bands; two are also decorated and inscribed on the back. They are painted on convex glass.

Jolliffe's bust-length profiles (which are of the usual size) were normally housed in frames of oval hammered brass or pearwood. As no advertisements or trade labels of Jolliffe, showing prices, have been seen, we do not know how much these glass profiles cost, but the price must have been higher than 2s 6d, which he was charging in 1758.

Two trade labels are recorded. No. 1, seen on the reverse of the large group of the Ashburnham family (c. 1767) illustrated in Section Two, reads as follows:

862

John Jolliffe

Bookseller

in St. James' Street

LONDON

Takes Likenesses

from the

Shadow.

Trade Label No. 2 was seen by W. P. Perkins on the reverse of the profile, painted on glass, discovered by him, which I mentioned above. It bore the address 72 St James's Street. Since this profile is later in date than the Ashburnham group, the label must have been used later than No. 1 (though it cannot have been used after 1795, when the numbering of St James's Street was changed and No. 72 was renumbered No. 70).

Ills. 56, 94, 245, 1102-1111, 1219, 1236

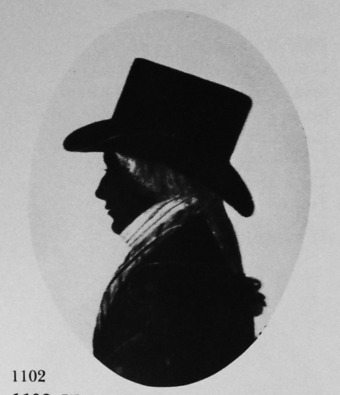

Unknown man

Silhouette painted on flat glass with black border; backed with silk

? Mid.1780s

Size (including border) 3 1/8 x 2 ½ in./80 x 64mm.

Frame: oval, pearwood

The sitter’s clothes suggest that he is dressed for riding.

M. A. H. Christie collection

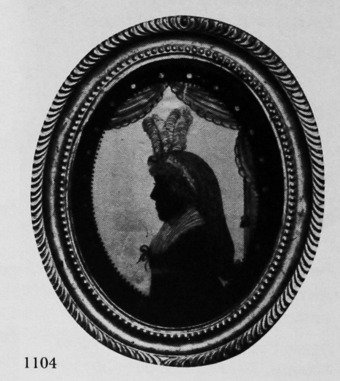

Captain Dewey

Silhouette painted on flat glass, with decorative black border; backed with silk

? Late 1780s

Size (including border) 4¼ x 3½in./109 x 90mm.

Frame: oval, hammered brass

J. A. Pollak collection

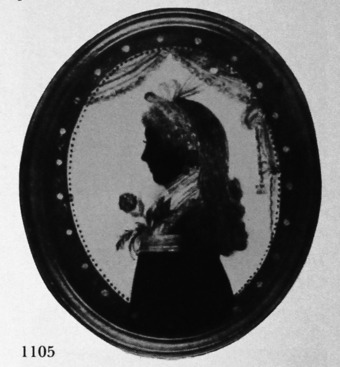

Unknown woman

Silhouette painted on flat glass, with decorative black border; backed with silk

c. 1788-90

Size (including border) 3¾ x 2¾in./96 x 70mm.

Frame: hammered brass

J. A. Pollak collection

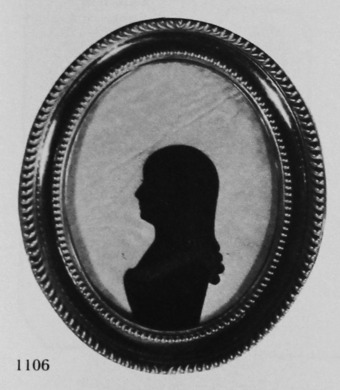

Mrs H. P. Roberts

Silhouette painted on flat glass, with decorative black border; backed with silk

c. 1790

Size (including border) 3¼ x 2¾in./83 x 70mm.

One of the two silhouettes that led to the mistaken identification of the artists as ‘H. P. Roberts’. The decorative band has been overpainted at the base of the silhouette.

From Weymer Mills, ‘One Hundred Silhouettes from the Wellesley Collection’ (1912), by courtesy of the Oxford University Press

Miss Mary Drewe

Silhouette painted on flat glass, backed with silk

c. 1792

3 x 2 ½ in./77 x 64mm.

Frame: oval, hammered brass

Mary Drewe, daughter of the Reverend Herman Drewe and his wife Sara Mary (née Hatherley), was born on 9 February 1780 at Combe Raleigh, near Honiton, Devon, where her father was rector (he was also the rector of Wootton Fitzpaine). She married the Reverend Lewis Way.

Silhouettes by Francis Torond of Mary Drewe’s aunts and uncles are illustrated in Chapter Six and Section two.

Author’s collection

Mrs Caled Morris

Silhouette painted on flat glass, with decorative black border; backed with silk

July 1795

Size (including border): 3½ x 2¾in./90 x 70mm.

Frame: pearwood

D. S. Patton collection

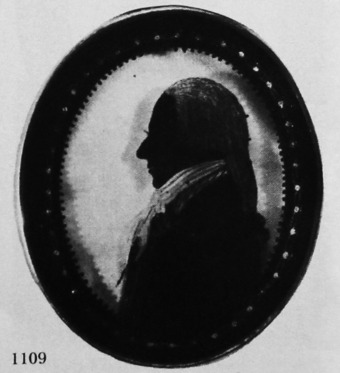

Pinchbeck locket, containing a silhouette of an unknown man painted on slightly convex glass (backed with silk), with decorative black surround, by W. J. Jolliffe, (?) late 1780s.

Size (including border): 1 ½ x 1in./39 x 26mm.

D. S. Patton collection

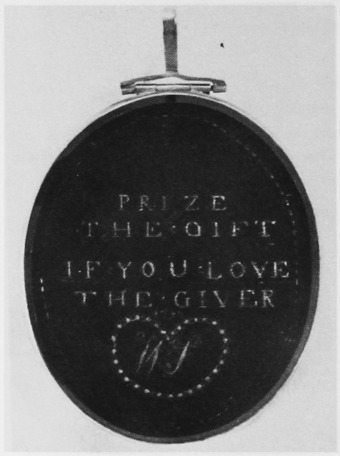

Gilt metal locket, containing a silhouette of an unknown man (‘W. S.’), painted on flat glass (backed with silk), with decorative black border, by W. J. Jolliffe, 1797. Size (including border): 2 ¼ x 1 ¾ in./58 x 45mm.

On the reverse are the inscription, ‘Prize the gift if you love the giver’, the initials ‘W. S.’ in a heart-shaped shield, and the year.

Author’s collection

Gilt metal locket, containing a silhouette of an unknown woman (‘S. P.’), painted on flat glass (backed with silk), with decorative black border, by W. J. Jolliffe, 1797. Size (including border): 2 x 1½in./51 x 39mm.

A companion to the silhouette illustrated in 1109, also with the date, the sitter’s initials, and a similar surround on the reverse. These two lockets were probably painted on the occasion of the marriage of the two sitters.

Author’s collection

Trade Label No. 1 of W. J. Jolliffe.

By courtesy of the Reverend John D. Bickersteth

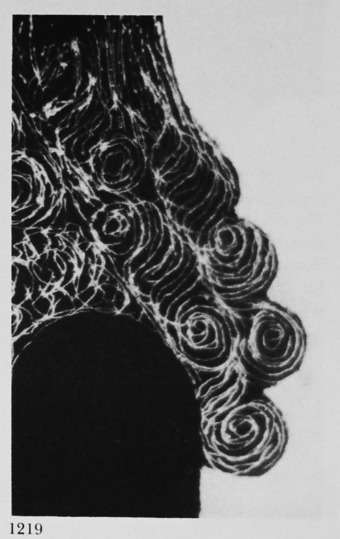

DETAIL

Woman’s hair. Detail from a silhouette by W. J. Jolliffe, showing subtler treatment than the silhouette by Abraham Jones of which a detail is illustrated in 1220. (1106)

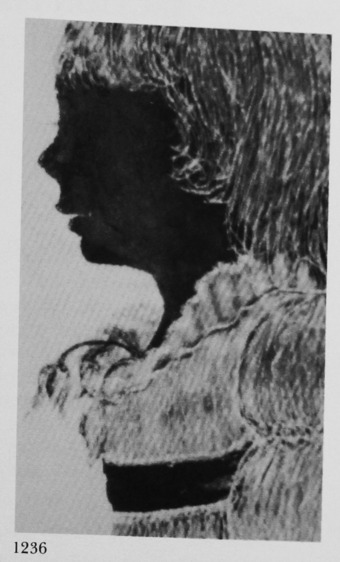

Part of a child’s dress.

Detail from a silhouette by W. J. Jolliffe. The silk backing gives an effect of stitching. (245)

D. S. Patton collection

Unknown young girl (aged five or six), dressed with notable elegance.

Silhouette by W. J. Jolliffe, c. 1794-95.

costume dating points

The length of hair and the fringe, typical for small girls of the period.

This plain muslin dress has a frill about the square neck-line, and the child’s mother has further embellished her appearance for her sitting to Jolliffe by the addition of a flower at the bosom.

The fathered sleeves, similar to those shown in 247, which bears the date 1796.

D. S. Patton collection

SECTION THREE

Decoration and inscription (‘Prize the gift if you love the giver’), scratched in black pigment with a needle on the under side of the glass of the reverse of a gilt metal locket, and backed with copper foil. The silhouette (1109) is by W. J. Jolliffe, 1797.

Author’s collection

Chapter 4

Unknown man

Silhouette attributed to W. J. Jolliffe, taken 1765-75.

costume dating points

The physical wig, favoured by members of the learned professions, and by doctors in particular, after the 1750s.

The three-cornered hat, the forward peak of which is high enough to suggest that it may be a Kevenhuller, which was still being worn by older men, such as this sitter, during the 1770s.

The absence of bows from the neckwear, which suggests that this is a stock, which was in fashion during the 1770s.

The absence of a line at the back of the neck (which would suggest a collar) implies that the sitter is wearing a coat. Since he is an elderly man, this might be a pre-1765 collarless coat which he had owned for some years.

R. Kilner collection

Chapter 8