Foster, Edward (McKechnie Section 2)

See also Sections Three, Four, Five, Six and Seven

Recorded by Jackson in The History of Silhouettes (where she lists him as Edward Ward Foster) and Dictionary. Other writers (including Foskett, who records him as a miniaturist) have erroneously listed Foster as Edward Ward Foster. It is clear, however, from the announcement of his death in the Derby Mercury, as well as from Robinson's Derbyshire Gatherings (1866), that Foster's only forename was Edward. Edward Ward Foster may have been the name of a son by his first marriage with Elizabeth Ward, and may have been the E. W. Foster recorded by Graves as having exhibited twenty-two landscapes at the Royal Academy 1812-28. I have derived some biographical information about the profilist from the Derbyshire Advertiser, 6 May 1921. See also Woodiwiss, 'Edward Foster, Derbyshire Silhouettist and Centenarian', Derbyshire Countryside, 8 November 1962.

The artist's father is said to have been steward to Sir Robert Burdett, of Foremark Hall, Derbyshire, and his maternal grandfather is said to have been Robert Howard, a younger son of one of the Dukes of Norfolk. Though not fully proved, these suppositions may be correct; not all younger sons are recorded in Burke's Peerage, and not many members of this ancient family were named Robert. Moreover, since the family name of the Dukes of Suffolk is also Howard, Robert Howard may have come from this family.

Edward Foster's father came from the same family of Fosters as John Thomas Foster, the first husband of the famous Lady Elizabeth Foster, daughter of the Fourth Earl of Bristol, later the second wife of the Fifth Duke of Devonshire. Her story has been told many times (for example, by Elizabeth Foster, in Children of the Mist, London, 1960). From whichever noble family he came, the artist's grandfather is said to have reached the age of 104 years, and his wife that of 103 years. Edward Foster (who himself lived to the age of 102) came, therefore, from a family with a tradition of longevity.

Robert Howard, having joined the Old Pretender's cause in 1715, was eventually driven into hiding by the fear of being arrested for high treason. He changed his surname to Hayward, and found employment in Derbyshire, first as a gardener, and then as a farm labourer. The family settled in Derbyshire, where, in the parish of All Saints, Derby, the profilist was born on 8 November 1762.

We know nothing of Edward Foster's childhood. When he was about seventeen, he joined the Derbyshire Militia as an ensign. Later he volunteered for service with the infantry of the line, and was given a lieutenancy in the 20th Regiment of Foot (the Lancashire Fusiliers). His initial spell of active service was spent, under the command of General (later the first Marquess) Cornwallis, in America during the final phase of the War of American Independence. He later saw extensive foreign service, accompanying the same regiment to Holland in 1799 under the Duke of York, and afterwards proceeding to Egypt. There his regiment formed part of General Sir Ralph Abercromby's army, whose task was to help drive the French out of Egypt. These operations culminated in the battle of Alexandria (1801), in which Sir Ralph was killed. His service abroad cost Foster some injury to his health, for he developed a severe eye infection, due either to the Egyptian climate or to the effect of sand particles. He was therefore posted home, in charge of a party of 104 wounded men. After his eye had recovered somewhat, he was ordered to Walmer at the period when a landing on our shores by Napoleon's troops was expected at any time. Nelson frequently visited Deal during these days, and often dined at table with young Lieutenant Foster. On 21 October 1805. the day of the Battle of Trafalgar, Edward Foster retired from the army at the age of forty-seven, having served since 1780.

Foster, then, was no longer a young man when he left the army. Having always been a good amateur painter, he now decided to put his talents to commercial use. No doubt he had already tried his hand at painting profiles while in the army; I have myself seen profiles of soldiers (with the sitter's face in black, and his uniform in colour) which have the appearance of Foster's work. Foster took first to portrait painting, at which he was immediately successful. He is also said to have been appointed 'Miniature Painter to the Royal Family', with the special patronage of Queen Charlotte, and of Princess Amelia, who died in 1810. When this Royal Appointment was granted, however, is not clear, since no Royal coat-of-arms appears to have been used on the artist's trade labels until c. 1817. Nevertheless, he was using a brass hanger, incorporating his name with the Royal Crown, apparently as early as 1811.

Otherwise, we know nothing of Foster's life from 1805 until c. 1810. It must have been during these years that he was allotted rooms in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle, and is said to have been intimate enough with some members of the Royal Family to have been invited occasionally to play a hand of whist with them. One may guess that during these years he was drawing master to Princess Amelia, after whose death he took up a full-time professional career, mainly as a profilist, although coloured miniatures by him must exist.

Since all trade labels seen include the words 'From London', it seems likely that it was in the capital that Foster began his full-time career as an artist, probably c. 1810. By 1811, however, he was in Derby, at Mr Abbot's, Trimmer, Friar Gate. By this time he had begun to use a mechanical means for the preliminary outlines of his silhouettes, and he became both prolific and well known. According to the Derbyshire Advertiser (loc. cit.) Foster invented his 'machine'. The poet John Ramsay addressed to him some complimentary lines, later to be plagiarised , or quoted, by at least one other artist (Gerard; see Section One) on a trade label:

First from the shadow on the polish'd wall,

Were took those faces which profile we call,

The first was drawn by the Corinthian dame,

Who, by the art, immortalized her fame.

From posture next improving on her plan,

The artist with the pencil took the man.

Yet oft the lines where blemishes prevailed,

Were taught to flatter, and the likeness failed.

But how to form machines to take the face,

With nice precision in one minute's space,

To paint with bold, unerring certainty

The face profile in shades that time defy,

Where all the likeness to agree,

This honour, Foster, was reserved for thee.

The 'Corinthian dame' is an allusion to Korinthea, traditionally regarded as the first profilist (see Chapter One).

Among Foster's activities was the preparation and publication of several educational charts for the use of schools: A Chronological analysis of the Old and New Testament, The Histories of Rome, France and Britain and A Chronological chart of the History of the British Empire. Foster presented no fewer than 5,344 copies of these charts, free of charge, to parish and other schools. The original manuscripts of some of them are in the Derby Museum.

Foster visited many parts of England; see below for a table (necessarily incomplete) of his travels. He seems intermittently to have continued painting profiles during the 1830s, by which time he had probably returned to Derby to settle down, since he had reached the age of seventy by 1832. That he still occasionally visited other centres is known from two advertisements in the Windsor and Eton Express (6 and 13 July 1838) announcing his intention to be available in Windsor.

Foster married five times. It seems virtually certain that he had seventeen children, only the youngest of whom survived him; this was Phyllis Howard Foster (q.v.), born when Foster was aged ninety in c. 1852. Woodiwiss ('Edward Foster, Derbyshire Silhouettist and Centenarian') states that Foster had sixteen sons and one daughter. The Derbyshire Advertiser (loc. cit.), however, states that he had sixteen daughters and one son. Some years after Phyllis's birth, a lady of Foster's acquaintance twitted him in verse:

Mr Foster married a wife, and then he lost her:

He married a second, and then a third,

And then a fourth, upon my word!

Laugh not, good sirs, for, I protest

A fifth is added to the rest,

And a fair daughter calls him sire;

At five score years you must admire,

My tale, if true —

Why, sir, I mean five score and two!

A public dinner was held in Derby by Foster's fellow-townsmen to celebrate the old man's hundredth birthday. It was presided over by the Mayor, and during the speeches which followed the meal many compliments were showered on the guest of honour. In a brief reply, Foster proudly assured his friends that he had 'never known what sickness meant' (he must have chosen to ignore his eye trouble), and that he was still able to earn his living. A grant of £60 was made to him from the Royal Bounty Fund on behalf of Queen Victoria, largely due to the good offices of Lord Palmerston. The last two years of his life were, however, marred by financial troubles. He died in Derby, in Parker Street, Lodge Lane, on 12 March 1864, aged 102 years and 124 days. Sadly, he was buried in the pauper's section of the Nottingham Road cemetery, where his grave is marked only by a number: 28819. Foster's last wife survived him.

A brief resumé of Foster's travels (mostly compiled from dated silhouettes, and inevitably incomplete) is given below:

1810 Possibly in London

1811 At Mr Abbot's, Trimmer, Friar Gate, Derby

1811-14 At some time during these three years in Macclesfield

1814-17 Touring in Derbyshire, Yorkshire and Lancashire

1819 Possibly at 125 Strand, London

1820 At Needham Market, Suffolk

1823 In Preston and Liverpool

1825 In Huddersfield

1832 In Windsor

Jackson quotes a passage about Foster, written by a friend who met him in 1863 and first published in Notes and Queries:

Numbers of silhouettes were done in Derby and the neighbourhood, and also in other parts of England, by a Derby man of the name of Edward Foster, who died in 1864, or in the following year. I knew him well, and in December, 1863, had a long conversation with him in his own house at Derby, he then being in the 102nd. year of his age. He was quite active and moreover a respectable and intelligent old man. He had been married several times, and at the time I speak of, he had a wife much younger than himself, and a daughter, of whom she was the mother, eleven years of age. He had had children by former marriages, but they were all dead, and he told me that if his eldest child, a daughter, were then alive, she would have been seventy-nine, or sixty-eight years older than her youngest sister!

Jackson also quotes excerpts from two advertisements. One excerpt reads as follows: 'FOSTER, Profilist, From London, Most respectfully informs his friends and the Public that he has taken apartments at ... for a few days only, where, by means of bis newly-invented machine he proposes taking Profiles.' The advertisement also quotes from another advertisement a reference to 'the machine making a complete etching on copper plate'. Woodiwiss (notebook) refers to another advertisement which mentions 'Profiles in Black, 5s. upwards'; this suggests that Foster was not producing 'red' work (see below), and that at one period (probably early in his career) he was offering only black work. A trade label used c. 1817 gives prices ranging from 5s to 10s. Although seen on a black example, the price of 1Os probably refers to the 'red' profiles, since there is no mention on the label of profiles on plaster or glass.

In considering Foster's work, we must bear in mind a few general points. The costume of his sitters suggests that extant labelled silhouettes or examples with 'Foster' hangers (that is, his professional works) date from c. 181 I until c. 1838, although later examples by this prolific and long-lived artist might come to light. Foster is known to have been a talented amateur artist before he began his career as a profilist. I have already mentioned Foskett's references to water colour work by Foster. Here, however, we are concerned with the surviving silhouettes, which are painted on card and fall into two categories: black profiles, and examples which are referred to as 'red' profiles.

To judge from the dress of the sitters, it appears that the black profiles are all earlier than the red profiles. Many of the earliest of the former have a short bust-line finish, terminating in a definite peak towards the front. Another finish, with a horizontal line of single concavity, has also been seen, not only on the black work but also on some of the red.

The black used was not dense, and details of hair and clothing were added in pigment mixed with gum arabic. This would cover the whole of the head, where the dark pigment was used to show the lines of the hair formation. Some of these profiles also have touches of Chinese white, used to show the decoration on a comb in a woman's hair, or the shape of the fashionable mancheron, worn first in the years preceding 1820.

Neckwear and shirt-frills are left clear of pigment, and the detail is painted in fine lines of thinned water-colour. (The 'three-dot' technique, typical of Foster, is seen more on the red profiles than on the black.) Sometimes Foster used a soft grey. All his work, whether black or red, is painted with extremely fine brush-strokes.

252

I have seen only one black silhouette with detail shown in gold.

774

Foster's 'red' profiles are so called because of the colour of their backgrounds, which varies in fact between a strong Indian (or Venetian red) and reddish-brown. These silhouettes are embellished in fine gold, covered with a fine layer of gum arabic. Even the gold with which a man's whiskers is shown is held by a touch of gum arabic. Over the years, this gum has peeled a little and some crazing (in very small pieces, because of the thinness of the layer of gum) has resulted. Sometimes Chinese white was also used and, on later examples, colour was sometimes used to indicate a cravat. Otherwise, shirt-collars and cravats on profiles of men were left white, with detail added finely in line, usually in thinned black pigment. On these profiles Foster used a 'three-dot' technique (which has often been referred to by previous writers) to show the effect of transparency on the women's dresses of his day. Both the crazing and the three-dot technique can be seen on one of the illustrations. The bust-line finish on the red profiles varies a good deal, and the short, sloping finish typical of the earlier black work is rarely seen.

792

It is known that Foster sometimes painted in colour. One profile of a soldier (with black face and uniform in colour), illustrated in Chapter Five, is, in my opinion, his work. All Foster's work, his red profiles in particular, have a special value because of the full and minute detail with which Foster shows the costume of his day; a number of them, moreover, are dated.

152

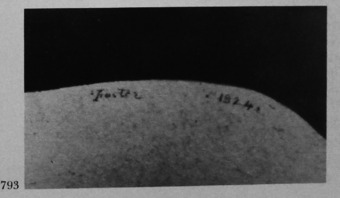

During his long career, Foster indicated the authorship of his work not only by signatures and trade labels, but also by brass hangers embossed with his surname. Trade labels will be discussed last. Two typical signatures are illustrated, one of them very small (though signatures of Foster even smaller than this have been seen). Some profiles are simply signed 'Foster', with or without the date; others, 'Foster pinxt.' These signatures are usually only found on the red profiles.

792, 793

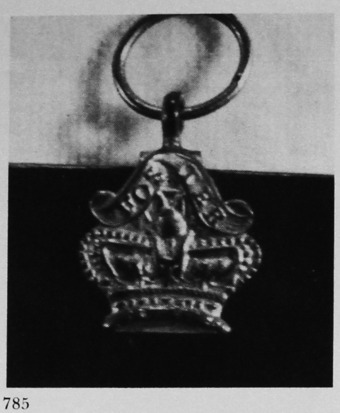

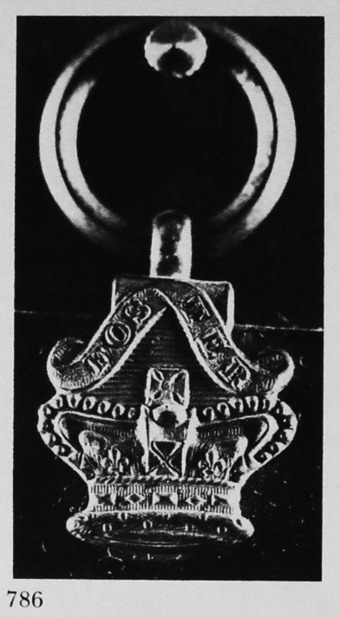

There are two types of brass hanger, bearing Foster's name above the Royal crown, on his frames. One, the larger of the two, was used on papier mâché frames measuring either 5¾ x 4¾ in. or 6 x 5 in. The other, smaller hanger, is seen on larger frames measuring 7¼ x 5¾ in. The larger hanger appears to have been used until c. 1816; the smaller hanger, until c. 1825 and possibly later. The papier mâché frames of silhouettes dating from the 1830s are usually without a 'Foster' hanger; they are smaller than the frames referred to above, and usually have ornate brass ovals and hangers with interesting decorative features.

785, 786

Foster used a number of trade labels at different phases of his career. Those which he appears to have used earlier in his career do not bear the Royal coat-of-arms; those which he apparently used later do bear it. As I have mentioned, all the labels bear the words 'From London'; I have suggested that the artist began his professional career in the capital, probably c. 1810 (since Jackson records a label bearing the address 'At Mr. Abbot's, Trimmer, Friar Gate' on a silhouette dated 1811). This trade label (No. 1) was noted in the Ms of an article by Woodiwiss, now in my possession. Jackson also records the address at 'Mrs. White's, Totnes', which she saw on what was probably the same label, used by Foster when travelling. As Jackson also records a London address at 125 Strand, it is possible that the artist was there in c. 1819. Trade Label No. 1 reads as follows:

MR. FOSTER

(FROM LONDON),

Respectfully informs the Ladies and Gentlemen of ... and it's vicinity, that he intends to execute [examples of his] mode of TAKING PROFILES, at Mr. Fox's ... the City of Antwerp Inn, by means of this ma[chine] he is enabled to take the Outline with such Truth as cannot be exceeded, being in itself incapable of error. It is so much the custom to exaggerate the merit of New Inventions, that when the true statement of them is being made it is scarcely believed. Mr. Foster would feel diffident in recommending this Instrument to the notice of the Public, were not the constructions of the Machine upon the most extraordinary and unerring Correctness: and the only true Method ever discovered, by which the contour of the human face is imitated; the momentary passions of the countenance are particularly expressed at the time they are delineated.

The construction and simplicity of this Instrument render [it] one of the most ingenious Inventions of the present day [and] it is totally impossible it can deviate from the Origina[l] in the smallest particular. Mr. Foster is the Inventor of the above-mentioned Ins[trument] [illegible] the privilege of which is secured to himself.

[gap in the text]

This instrument is opened for the Inspection of any Lady or G[entleman] at the inventor's [illegible] Apartments, independent of Orders.

Profiles copied and reduced, with [remainder missing]

This label was obviously used immediately after Foster invented his machine, which he then used outside London.

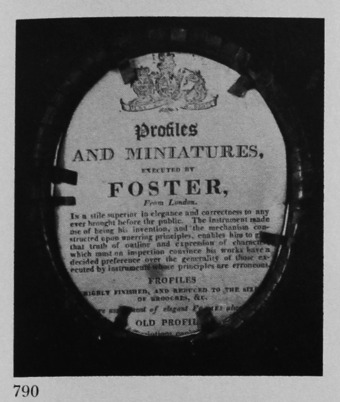

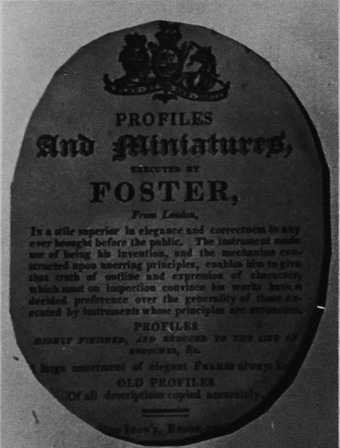

Trade Label No. 2 (illustrated), printed at Macclesfield, is placed next in chronological order, since it bears no Royal coat-of-arms. It has been seen only on black profiles painted c. 1811-14, either with or without the larger type of hanger.

787

It reads as follows:

PROFILES

Executed by

FOSTER

From London.

In a stile superior in elegance and correctness to any ever brought before the public. The instrument under use being of his own invention, and the mechanism constructed upon unerring principles, enables him to give that truth of outline, and expression of character , which must on inspection convince his works have a decided preference over the generality of those executed by instruments whose principles are erroneous.

PROFILES highly finished on PLAISTER, GLASS and PAPER, that will stand for any length of time, and reduc'd to the size of Lockets, Broaches, &c.

A large assortment of elegant FRAMES and GOLD BROACHES always kept.

Old Profiles of all descriptions copied accurately.

Mr. F. Makes it a rule not to allow any person to have the profiles of any Lady or Gentleman till he is satisfied the parties have no objection.

J. WILSON, PRINTER, MACCLESFIELD.

Since this is the only label that offers silhouettes on plaster and glass it seems that any surviving profiles on these media would date from well before 1820. Trade Label No. 3 (illustrated) as printed for use at Harrogate,

c 1817, after three years which Foster had spent in Derbyshire, Yorkshire and Lancashire.

789

The long dashes indicate missing text where the label was trimmed to fit the oval. The label reads as follows:

MR. FOSTER

Profilist

FROM LONDON

Most respectfully informs his Friends and the Public, that he has removed from the Promenade, to Mr. Batchelor's, adjoining Hargrove's Library, High Harrogate, where, by means of his newly-invented Machine, he Purposes TAKING PROFILES of any Lady or Gentleman, accurately precise in Resemblance, and executed in a Stile superior to any ever brought before the Public.

The Construction and Simplicity of this Instrument render it one of the most ingenious Inventions of the present Day, as it is impossible it can deviate from the Original.

The practice Mr. F. has experienced for the last Three Years, in the Counties of Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Lancashire, will, no doubt, in some Measure, introduce him to the Notice of the Inhabitants of, and Ladies and Gentlemen resorting to Harrogate and it's Vicinity: and for further Satisfaction, Mr. F. pledges his Word that he will respectfully return the Money paid, if the Likeness produced is not good.

Attendance from Ten till One, and from Two till Six

Profiles from Five to Ten Shillings, exclusive of Frames; a large Assortment of which is always kept.

Specimens to be seen at HARGROVE's Library, Mr. ROB

⎯ PROMENADE-ROOM, and at Mr. F's Apartments

Time of sitting will not exceed ONE MINUTE

— man admitted to see the peculiar —

— Instrument, at any —

Trade Labels Nos 4 and 5 (both illustrated) bear the same text, but are different in typography. Both were used by Foster when touring the provinces. No. 4 appears to have been used during the early 1820s; No. 5 later in the 1820s and in the early 1830s. The illustrated example of Trade Label No. 5 is from a red profile of a woman in the M. McI. Ayrton collection.

790, 791

It is evident that the five numbered labels do not constitute the complete series, for Jackson refers to another label, headed by the Royal coat-of-arms and possibly used during the 1820s. This included the phrase:

Modern Style of Executing profiles sanctioned by the Principal Nobility of the Kingdom.

FOSTER

From London— [label trimmed]

Foster does not seem to have used trade labels throughout his career, and no label known to have been used during the 1830s has come to light.

Occasionally a silhouette may be found, neither labelled nor signed, and without a hanger embossed with Foster's name, which can yet be attributed to him on account of pieces of card behind the profile. It was Foster's practice to fill up the oval behind his profiles, which were nearly always covered with convex glass, with scraps of the card from which the ovals had been cut.

794

It is clear from the shapes of such fragments that the profiles were first painted on rectangular pieces of card. Locks of (presumably) the sitter's hair have sometimes been found among such fragments, which may also bear sketches for other profiles.

Ills. 135, 152, 198, 201, 202, 205, 208, 252, 771-794

Officer of the British infantry

Silhouette by an unknown artist (possibly Edward Foster), early nineteenth century.

This silhouette, on which the uniform is painted in colour, does not show the officer’s badge of rank. The sash, tied on the left, indicates that he is an infantry officer, and his red coat, with blue facings, that he is a member of one of the Royal regiments. Since he is wearing the crescent-shaped hat which, after 1900, was discarded for the shako by all but senior army officers, his rank is presumably above that of major.

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

Chapter 7

Unknown woman

Silhouette by Edward Foster, c. 1814.

costume dating points

The turban, fashionable at this time, small and plain for daytime wear and more decorative for the evening.

This example is apparently designed for the daytime.

The dress of flimsy material, with a columnar neck and single ruff. It is not clear whether the ruff is a fill-in or part of the dress.

Author’s collection

Unknown woman, probably in evening clothes

Silhouette by Edward Foster, probably 1818.

costume dating points

The half-handkerchief, draped over what is probably an à la Titus hair-style, and hanging down at the back.

The low décolletage of the dress, worn without a fill-in, suggests evening wear.

From the collection of the late J. C. Woodiwiss

Miss Musgrave

Silhouette by Edward Foster, probably c. 1818.

costume dating points

The position of the knot in the hair is considerably lower than in 205 (about two years later).

The short necklace, in fashion at about this date.

The top of the dress (apparently worn for evening) is narrower at the shoulder than that shown in 205.

Author’s collection

Unknown woman

Silhouette by Edward Foster, probably c. 1820.

costume dating points

The position of the knot of hair on the back of the head, rising from the nape of the neck, but not quite as high as the Apollo knot of a year or two later.

The hair is dressed for the evening, since there is an added ringlet behind the ear.

The evening dress shows puffing at the shoulder (to increase considerably later in the decade).

The waist-line, at this date, is still higher than its natural position.

M. A. H. Christie collection

Unknown woman, perhaps in her early thirties

Silhouette by Edward Foster, 1829.

costume dating points

The bonnet, complete with both bavolet and chin stays, which appeared right at the end of the 1920s.

The ruff: an interesting late example.

The sleeve of the dress is full at the shoulder; it is probably the gigot.

Author’s collection

Chapter 9

Unknown boy (aged about twelve)

Silhouette by Edward Foster, c. 1811-14.

costume dating points

This boy, older than the sitter in 253, wears his hair in the à la Brutus style worn by men at the time.

The narrow frill is turned down at the neck.

The tail-coat, similar to the style worn by men at the time; there is a button-hole in the left lapel (fashionable for men at the time).

Author’s collection

SECTION TWO

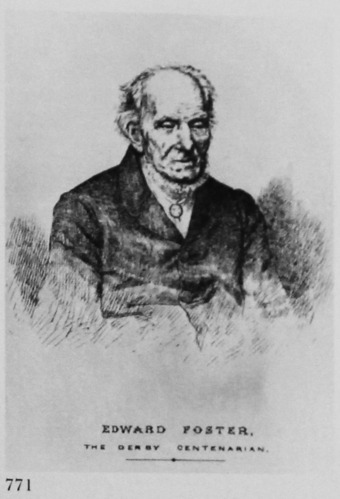

Edward Foster at the age of a hundred. Print by an unknown engraver, 1862.

From Robinson, Derbyshire Gatherings, 1866

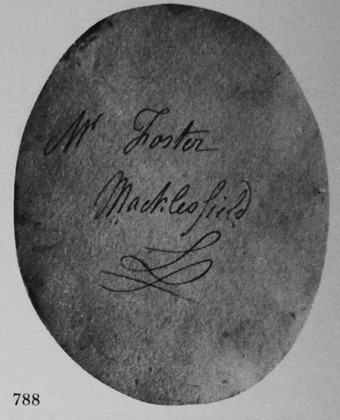

William Snell Magee

Silhouette painted on card

c. 1811-14

3 7/8 x 2 5/8 in./99 x 67mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with the larger type of embossed hanger

Taken at Macclesfield (the card is inscribed on the reverse ‘Mr. Foster, Mackesfield’). The sitter’s cravat and shirt-frill are painted in line.

Author’s collection

Mrs Magee

Silhouette painted on card, with detail in Chinese white

c. 1811-14

3 7/8 x 2 5/8 in./99 x 67mm.

Trade Label No. 2

Frame: papier mâché, with the larger type of embossed hanger

Taken at Macclesfield, like the companion silhouette (772) of the sitter’s husband.

Author’s collection

Unknown woman

Silhouette painted on card, embellished with gold

c. 1814

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

Trade Label No. 2

The artist has employed his characteristic ‘three-dot’ technique in rendering the sitter’s dress.

From the collection of the late J. C. Woodiwiss

Unknown woman

Silhouette painted on card, with detail in gum arabic and Chinese white

? c. 1817

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

Trade Label No. 3

Frame: papier mâché, with the larger type of embossed hanger

The white dots on the sitter’s shoulder probably indicate a mancheron.

Author’s collection

Mr Musgrave

Silhouette painted on card, bronzed on a red ground

c. 1818

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with the larger type of embossed hanger

Author’s collection

Mrs Musgrave

Silhouette painted on card, bronzed on a red ground

c. 1818

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with the larger type of embossed hanger

For a silhouette by Foster of the Musgraves’ daughter, see 202.

Author’s collection

Mrs Entwistle

Silhouette painted on card, in gold on a Venetian red ground

1824

2¾ x 2½in./70 x 64mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with decorative surround and cornucopia hanger

Signed ‘Foster’ in exceptionally small handwriting under the bust-line near the centre. For a silhouette by Foster of the sitter’s husband, see 135.

Author’s collection

Unknown man

Silhouette painted on card in gold, on a red ground

c. 1819

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with the smaller type of embossed hanger

Signed ‘Foster 125, Strand, London’.

M. A. H. Christie collection

E. B. Beck, of Needham Market, Suffolk

Silhouette painted on card, bronzed on an Indian red ground, with detail in Chinese white

1820

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

The use of Chinese white to render the highlights of the sitter’s hair is of especial interest. The space behind this silhouette was filled with pieces of card, in the manner typical of Foster.

Author’s collection

Mrs Symonds

Silhouette painted on card in gold, on a brownish ground

1823

3¾ x 3 1/8 in./96 x 80mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with vine leaf hanger

An outstandingly fine silhouette.

Signed and dated below the bust-line.

Author’s collection

Mr Wild, of Liverpool

Silhouette painted on card in gold on a brownish ground

1823

3¾ x 3 1/8 in./96 x 80mm.

Frame: papier mâché, with vine leaf hanger

The sitter, an older man, is wearing a part-wig and shirt-frill both of which were unfashionable at this late date.

Signed and dated below the bust-line.

Author’s collection

Robert Clay

Silhouette painted on card, in gold on a red ground, with detail in blue

3 December 1833

3¾ x 3in./96 x 77mm.

? Trade Label No. 5

Signed ‘Foster pinxt.’ Below the bust-line and dated on the reverse.

The sitter’s stock is painted in blue.

From the collection of the late J. C. Woodiwiss

William Coffee

Silhouette painted on card in gold, on a red ground

1833

3¾ x 2¾in./96 x 70mm.

Signed below the bust-line ‘Foster pinx. 1833’, and inscribed on the reverse. ‘Coffee./The celebrated Modeller, for/a long time employed at the/Derby china Works./

By/Foster/The Derby Centenarian.’

Coffee was of mature years when he was first employed by William Duesbury in 1791, and he is known to have been working independently in Derby as late as the autumn of 1810. Some time after this he worked in London, and then is said to have settled in the United States. Since he spears to be aged between forty and fifty on this silhouette (dated 1833), it seems likely that Foster took an original silhouette of Coffee in black in Derby in c. 1811, and later, in 1833, made a ‘red’ copy of it.

M. A. H. Christie collection

The two types of hanger used by Edward Foster on his frames: the larger type, used c. 1811-16, and the smaller type, used c. 1817-25, and possibly later.

Author’s collection

Trade Label No. 2 of Edward Foster.

Author’s collection

Inscription on the reverse of a silhouette (772) by Edward Foster; the silhouette by Foster of the sitter’s wife (773) bears Trade Label No. 2.

Author’s collection

Trade Label No. 3 of Edward Foster, from the silhouette shown in 775.

Author’s collection

Trade Label No. 4 of Edward Foster.

M. A. H. Christie collection

Trade Label No. 5 of Edward Foster.

In the possession of Major M. McI. Ayrton

Detail of ‘red’ silhouette (778), embellished with gold, of a woman by Edward Foster, showing the ‘three-dot’ technique with which he indicated the texture of the sitter’s costume, the fine crazing, typical of his work, and an example of the small version of his signature.

Author’s collection

Detail of ‘red’ silhouette (135), embellished with gold, of John Entwistle (whose wife is shown in 774) by Edward Foster, showing the artist’s signature, with the date.

Author’s collection

Fragments of card used by Edward Foster to fill the space behind one of his silhouettes.

Author’s collection